Why does adaptive divergence only sometimes result in speciation?

Speciation is the process by which reproductive isolation – typically comprised by multiple reproductive barriers – evolves between two taxa. Reproductive barriers come in many forms and most undoubtedly evolve as a byproduct of adaption of populations to different environments. However, ecological divergence does not always result in full reproductive isolation and speciation, as observed in species with locally adapted populations that are connected by some gene flow. I took a comparative approach using species in the serpentine flora of California to understand why divergence across serpentine/non-serpentine soils sometimes lead to speciation and why it sometimes does not.

Serpentine soils are tough environments for plants. Chemically, they have high heavy metal, high Mg, and low Ca concentrations, making for a chemical profile that can cause morality at early life stages. Physically, serpentine soils are often rocky with low organic matter, which often result in a drought-inducing environment. Despite these challenges, wherever serpentine occurs in the world (which is a lot of places), there are plants that have adapted to these soils; some of which are “endemics”, i.e., they only occur on serpentine. Other serpentine-associated species are known as “tolerators”, meaning that some populations occur on- and some off-of serpentine.

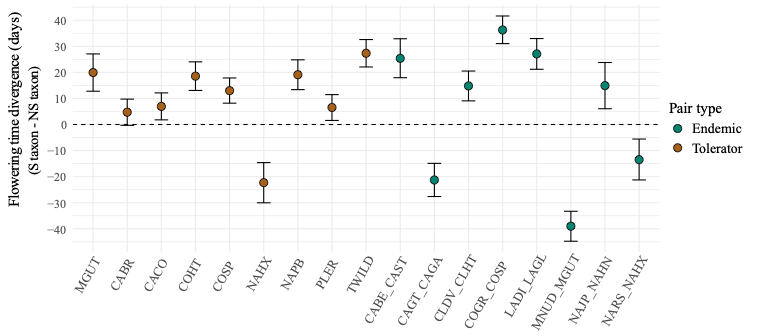

I constructed 17 pairs of serpentine-nonserpentine populations that either represented populations within a species (“tolerator” pairs) or populations between sister species (“endemic” pairs) to test a variety of non-mutually-exclusive alternative hypotheses about why ecological divergence only sometimes leads to speciation. I used nine tolerator sister taxa pairs and eight endemic sister taxa pairs. All species were annual and they spanned nine genera and six families.

Shifts in flowering time are often involved in adaptation to stressful environments. I tested the hypothesis that speciation is more likely to occur when shifts in flowering time are strong and more genetically-based versus plastic. I used a greenhouse-based reciprocal transplant to quantify flowering time shifts, and the degree to which they’re genetically based, in the endemic and tolerator pairs. I found that shifts associated with serpentine taxa are common and largely genetically-based, regardless of whether sister taxa were from endemic or tolerator pairs. This result suggests that, while flowering time shifts do not promote speciation per se, they may be important in causing enough reproductive isolation to facilitate adaptive divergence. Check out our paper on this here.

Local adaptation is thought to come with a cost; after all, no individual can have high fitness across all combinations of time and space. Costs to adaptation can promote speciation through habitat isolation, wherein costs associated with adaptive divergence prevent taxa from migrating and successfully reproducing in each other’s habitats. However, whether these costs exist in contexts relevant for speciation, how severe they are, and what the selective are that mediate fitness costs is not always clear.

One cost of serpentine adaptation is hypothesized to be a loss in competitive ability, which was originally posed to explain why serpentine endemics species don’t expand off serpentine. A trade-off between serpentine adaptation and competitive ability could decrease gene flow and promote speciation of endemics. As a corollary, we would predict that there is a weak trade-off between serpentine adaptation and competitive ability in tolerator species, where serpentine and nonserpentine populations are still connected by some gene flow. I performed the first multi-species test of competitive ability across serpentine endemics and serpentine tolerators and found that, indeed, serpentine endemics are worse competitors than serpentine tolerators. Stay tuned for more on this story!

Serpentine habitats come in many flavors – while they all have some hallmark features, like the low Ca:Mg ratios, they can vary in slope, degree of soil/organic matter buildup, water availability and coexisting communities. It may be that plants adapting to a relatively chemically-benign and competitive serpentine habitat (like a serpentine grassland) may experience different costs to adaptation than plants adapting to a harsh, extremely rocky serpentine habitat. I tested the hypothesis that endemics occur in harsher habitats by sampling two main aspects of serpentine and nonserpentine habitats – soil chemistry and texture, and the competitive environment. I found that endemics occurred in chemically harsher environments than tolerators, specifically in soils with lower soil Ca, which is thought to be one of the most limiting chemical challenges in serpentine. I also found that endemics occurred in habitats with more bare ground, which serves as a proxy for less-competitive environments, and is consistent with my greenhouse study showing that endemics had lower competitive abilities than tolerators. Check this study out more here!